Back To School With A University Press

Maybe I've been looking at getting published the wrong way. The manuscript is engaging yet, as non-fiction, it could also be classed as a resource. Why not try publishing via a university press?

Before long, this Substack may simply turn into a resource for the many avenues there are for getting a book published. That’s right, I’ve found yet another one. A few weeks ago, I went on a Teapot Tour with my girlfriend along some of the canal paths in Stoke-on-Trent. The tour aims to raise awareness of the heritage in the local area and the dutiful possibility of restoration. Plans already seem afoot to build a shopping village on a derelict pottery factory.

Yes, the area lined by canals may well be known as The Potteries but it needs updating. Vacant sites, that once produced the wares that made the area world-renowned, now need repurposing.

It was a fascinating tour, yet I was about to get a whole lot more invested. At the end, we sat down for refreshments and one of the attendees introduced himself. Andrew Spinoza then introduced his book, ‘Manchester Unspun: How a City Got High on Music’. The Northern powerhouse currently enjoys investment from the Middle East with gleaming skyscrapers yet, back in the Seventies, the city was in the doldrums, similar to how Stoke is now. With a few photos, Andrew demonstrated how change can occur, once you work out a niche to exploit. For Manchester, it’s music. Instead of chatting about a city’s renaissance as the subject of his book, I got talking about how to get a book published.

The book is a fascinating read and should be made available to each council as a guide to regeneration. I also learned that, despite the specific context of the book and its focus on music, Andrew doesn’t have an agent and his proposal was ‘rejected or ignored by all the big music agents and publishers’. But he found a publisher in Manchester University Press and a university press could be my refuge.

The Recognised Process Of Publishing Via A University Press

There’s not a whole lot of difference to publishing with a university press. Look at them as an independent publisher that takes unsolicited proposals. They still pick and choose what they print but without the tight niches that an established publisher may employ (especially if those niches are centred on celebrities and MPs as seems to be in fashion). You still have to submit a book proposal, which comes with its own guidelines. There are still commissioning editors for each subject area and even house-style guidelines.

I’d still need to entice the publisher to my book, including the title, and offer a short ‘elevator pitch’. NB, an elevator pitch is a succinct explanation of the essence of your book in the time it takes when talking to someone in an elevator before you exit. I already know that there isn’t a book about the New Yorkshire Wave, though there are several unauthorised biographies of Arctic Monkeys. Given I’ve done ANOTHER edit of the manuscript, I doubt it’ll peak above 180,000 words so there is a sense of completion. You can also expect to include a writing sample so none of that is any different.

Essentially, I still need to add to my 35-odd proposals and ensure I send it to the most appropriate individual. There may be an expectation for a university press to publish works from those who work and teach at the university itself, but one works to boost a regional author too.

The Peer Review Process

The Peer Review process can be considered a specific, named part of the university press approach. Established publishers may well have teams that get together to review proposals yet that’s kept in-house. With a university press, there is such a leaning towards academia that the individual faculties have an invested interest in what gets published. That typically means an acquisitions editor reviewing proposals and talking with a series editor, or even asking a selection of academic scholars to review them, based on the specific subjects the book is focused on. Essentially, that department wants to ensure that publications, especially academic ones, are aligned to their faculty are of a warranted quality.

Whenever I submit a proposal, I typically leave a final line, which reads ‘thank you for your consideration, please note that I have submitted to several literary agents and publishers’. This one line is to make the reader aware that exclusivity is still an option. At a university press, a reviewer may be so intrigued by the proposal and subject it concerns, that they tell the author not to simultaneously send it to other presses or publishers.

After the series editor and/or academic scholars have made their comments, the acquisitions editor can ask the author to take a look at the suggestions. At this point, a request can be made for approval from the university press itself. If approval is granted, a publishing contract can be drafted. As you’d expect with an established publisher, you can largely forget wiggle room and negotiation. All in all, the peer review process can take a couple of months or last up to a full year. Some universities even have committees that oversee the final peer review process, though few reject a manuscript that has gotten that far.

After that, there’s still time to make the requested changes and deal with image permissions. Cover design still needs to be confirmed, as does copy editing, proofreading, and final production, which will add a few months. You would also expect to assist with marketing around six months before publication. To ensure a personal approach, a questionnaire is completed. In the few weeks before publication, there’s still time to proofread the book and amend some minor design and layout details.

The Considerations Of A University Press

Many publishers select their manuscripts on commercial viability, university presses are a little different. Their expected niche is academic books and journals, which aim for an intellectual and/or creative impact. They can also publish works that are of regional interest and geared towards a general audience. Sounds a lot like my manuscript.

Arguably, their consideration may even be broader than an established publisher. The business model is based on book sales, yet the vast majority of university presses operate on a not-for-profit basis. Money also comes in via subsidies and grants so, while commercial viability is still a prerequisite, it may not be so dictating.

Publishing Experience

Granted, there are some well-established publishing houses that I would love to publish from. Penguin have been publishing since 1935 and Faber & Faber since 1929. However, the oldest publisher in the UK is… Cambridge University Press which has been going since 1534. That’s some experience and expertise, with it comes global presence and trusted relationships. Even with that lineage, you can still expect digital publishing platforms and a future-facing ethos.

A university press also keeps a close eye on sales. You’d expect that given how their money comes in from direct revenue and grants. That’s largely why their printing is so conservative. Once stock gets low, a reprint gets issued which seems more sensible than printing an excess amount only to let it sit on the shelf. You can tell there’s more of a thought process and commitment to keeping a book in print for longer.

Marketing

Ah yes, marketing. As with any publisher, the scope of their marketing has a lot to do with their in-house marketing department and how much they believe in your book. A university press will still want to sell as many copies of a book as possible. Their reach may not be as far yet they still organise book launches, send out books for review, or enter them into awards.

My Reasons For Considering A Publishing Press

Locality

There is a tangible London-bias with the established publishers in the UK. Therein lies a major stumbling block for my book. Whenever I look at the music section at a bookshop, a lot of the books tend to be focused on a couple of well-worn subjects. Namely, the Punk scene (largely around London) and The Beatles. Granted, two of this country’s main musical exports yet there is surely room for regional diversity. Both Cambridge and Oxford have established university presses yet so does Manchester University, and the universities of Sheffield, Leeds, and York, collectively as White Rose University Press.

That locality may give my book the edge and differentiate it from established publishers who see it as ‘too regional’. Of course, most books need to fit a niche yet those established publishers will be looking for those niches to sell in the millions. Whether that’s an unreasonable niche or a contradiction in terms is anyone’s guess.

A Natural Home

University presses may seem an unorthodox avenue for publishing but can be more of a natural home for books that do not have such a broad appeal. Certainly, for a book centred on a regional music scene, that would seem a much better fit. That fit may even be more persuading than the lack of an advance given they ‘get it’. Trust goes a long way, especially now I have a recommendation from a published author.

Reputation

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, notably Vanity Publishers, exploitation is an issue in getting a book published. Some publishers seem too good to be true yet with a university press you can expect a rigorous process and an element of credibility. My niche is on a specific music scene which gives me authority on the subject, and even name recognition. I could also expect the book to be sold extensively in a specific region, hopefully in Yorkshire (hello White Rose University Press).

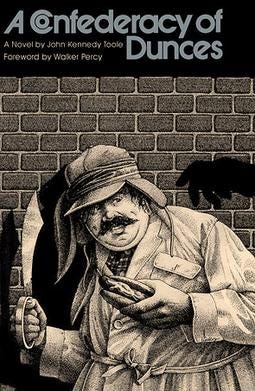

Consider that one of my favourite books, A Confederacy of Dunces, by John Kennedy Toole was rejected by Simon & Schuster. The book was released after Toole’s suicide, not by an established publisher but Louisiana State University Press. Toole did not know it but he had written a Pulitzer Prize-winning classic. All because a university press took a chance. The focus is not so much on creating a popular, commercially successful book, but one of creative or intellectual merit for a specific audience.

Experts

You may expect a university press to be focused on scholars and teachers, largely from the university itself. You’d be wrong, university presses align themselves with experts in their field which can include journalists. Ok, I do not count myself currently as a journalist yet I was one for The Sheffield Star when the New Yorkshire Wave occurred. If that doesn’t make me an expert on that music scene, I’m not sure what does.

I did picture a university press as one that dealt with age-old academic topics. Archaeology, humanist studies, and the works of Dickens, solely written by professors who are well past their retirement age, yet you would be surprised. Ok, so they do tend to center on an academic audience, which you could expect, but they also need to profit from book sales. They also include non-academics. That means there is a focus on a general readership too, from a vast array of subjects. Including non-fiction and music.

The conventional route to publishing a successful book typically follows a strict, tried and tested route. Get a literary agent, score a huge advance, sell millions of copies, and wait for the award show invitations. That’s largely a fantasy for almost any prospective author but a university press can offer a route to publication.

A university press typically operates like any independent book publisher. They take in proposals, select the ones they believe have the most promise, and publish them. My manuscript is based on a great idea, is well-researched (one part has over 250 references alone), the writing is compelling and the anecdotes add authenticity. That should mean a university press could pick it up, so excuse me while I get going with another submission. If it’s good enough, my manuscript will see the light of day.